The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is a shipping lane between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean along the Russian coast of Siberia and the Far East, crossing five Arctic Seas: the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea and the Chukchi Sea. This route offers significant savings between the far east and Europe being 30% shorter than via the Suez Canal and roughly 50% shorter than via the Cape of Good Hope. However, while the impact of man-made global warming has seen an alarming reduction in ice cover over recent years, the actual ice volume fluctuates annually depending on weather patterns and early freezing this Winter has taken some by surprise.

Typically there is only a 2 month span covering August to September where sea ice is minimal, with early September currently being the peak time for transiting the Arctic, but in recent years use of the NSR by shipping has extended to October and even November. Figure 1 shows the degree of trafficability for August and September for the NSR over the last few decades fluctuates inter-annually. This fluctuation is heavily influenced by weather patterns, especially those during the Summer and onset of Winter.

Figure 1. Northern Sea Route trafficability 2002-2018. Source: Wagner et al., Polar geography 2020.

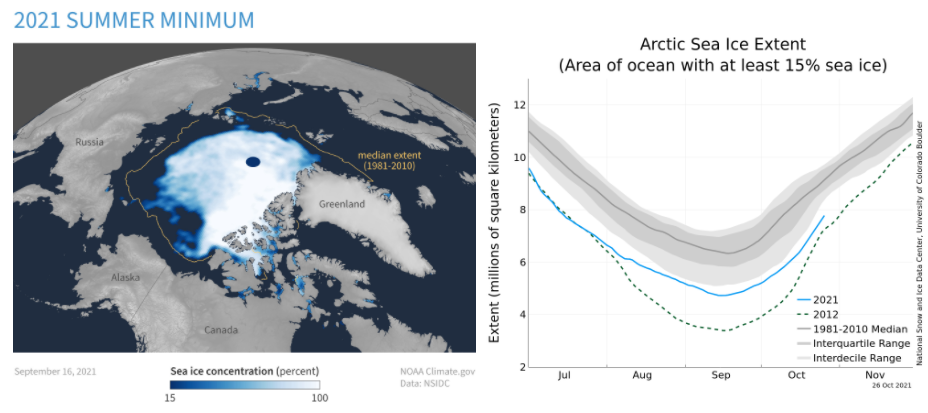

Despite that 2021 has been the warmest summer on record, the Arctic Sea was relatively cool and windy compared to recent years. Figure 2 shows that September’s ice extent was the highest since 2014 and was the 10th lowest ice extent in the 43 year satellite record according to the National Snow & Ice Data Center. So Summer 2021 has been unusual with lower temperatures and record low multiyear ice, and represented roughly one-fourth of the amount seen in the early 1980s. Also, waters around the New Siberian Islands as well as the archipelago of Severnaya Zemlya still had some white sheet/pancake ice left in mid-September.

Figure 2. 2021 Sea ice summer minimum concentration and extent comparison for 2021. Source: Left WMO and Right: National Snow & Ice Data Centre.

However, since the extent of annual ice recovery in winter is dependent on global weather patterns during the summer and the cooling down period, then even a completely ice free summer can be followed by an early onset of winter and a return to near full or full ice cover. Notably, recent research indicates that despite Arctic sea-ice being in decline it can still fully recover within 2 years. And that is exactly what has happened this year with cooler conditions present in the Summer and Autumn leading to earlier and more ice formation than average. This early freezing has taken Masters, shipping companies and even the Russian authorities by surprise with a number of vessels struggling or becoming stuck in thicker than expected sea-ice.

The latest ice map at Figure 3 from the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Research Centre shows that major parts of the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea are already covered by sea-ice that is up to 30 cm thick. In the eastern parts of the East Siberian Sea some areas extend to 70 cm thick one-year old ice and 2 meter thick multi-year ice. The Barents Observor reported 8 November that more than 20 vessels were currently either stuck or struggling to make it through increasingly thick sea-ice, and that the Russian authorities were sending 1-2 ice-breakers to the region. It reported yesterday that some 15 ships had since become stuck and were still awaiting help.

Figure 3. Sea-ice on the Northern Sea Route in the period 7-9 November. Source: aari.ru

Looking Ahead

In looking ahead Figure 4 shows that some climate models are not projecting guaranteed ice free waters until approximately 2050 or later depending on the degree of global warming attained. However, since there remains a strong seasonal and annual variability component then multiple ice free years may be possible from as early as 2040.

Figure 4. September Arctic Sea ice area (106 km2). Source: IPCC 6th Assessment Report.

So what does this all mean? Continued global warming and vanishing sea-ice is providing Russia the opportunity to invest heavily in infrastructure to develop NSR into a major shipping lane. Table 1 clearly demonstrates significant savings will be possible based on a speed of 12.5kts and 24mt p/day consumption.

Table 1. Comparative costs for NSR, Suez and Cape of Good Hope. Source: Fleetweather.

To enable these savings to be utilised sooner rather than later Russia plans to build a major fleet of nuclear powered icebreakers that will have enough power to traverse any part of the Arctic Ocean all year round.

Meantime, the early freeze this winter is a good reminder of the inherent risks involved and mother nature having the last say.

Stay safe and connected.