After forecasting last year’s record breaking hurricane season in the North Atlantic, it is time to take a sneak preview of what we can expect for the fast approaching 2021 season which runs 1 June to 30 November.

According to NOAA and CSU, up until 2020 the average Atlantic season has 12 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes (Cat 3-5), and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 66-103 units. NOAA has recently updated the set of statistics used to determine when hurricane seasons are above-, near-, or below-average relative to climate record. The updated averages have increased to 14, 7 and 3 respectively. There is no change for the Eastern Pacific basin of 15, 8 & 4 and the Central Pacific basin of 4,3 & 2 respectively. For comparison, the 2020 record breaking Atlantic year had 30, 13 and 6 systems!

The main factors to look at for the Atlantic are El Nino/La Nina (ENSO), the West African Monsoon (WAM), tropical and subtropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SST) and Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE).

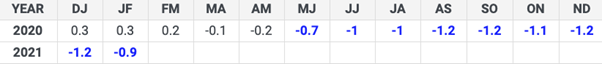

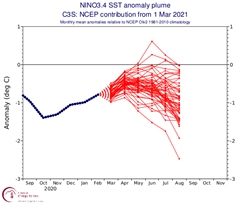

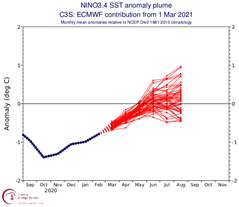

ENSO

El Nino tends to inhibit hurricane activity with increased vertical wind shear while La Nina has less vertical shear so brings more favourable conditions for tropical cyclone development. The current ENSO event began developing prior to the peak of the 2020 Hurricane Season and has continued unabated since. It has experienced some weakening in recent months.

Modelling guidance anticipates continued warming through the northern hemispheric spring. Model uncertainty increases as forecasts reach the beginning of hurricane season. The ECMWF climate forecasts show continued warming to ENSO neutral, while the NCEP climate forecasts show a reversal of the current warming trend with La Nina returning by the beginning of peak season. Both centres expect to come into agreement with ENSO neutral as we progress into the latter half of spring. Tropical Atlantic SST are close to their long-term average, while subtropical Atlantic SST are much warmer, favouring an active season.

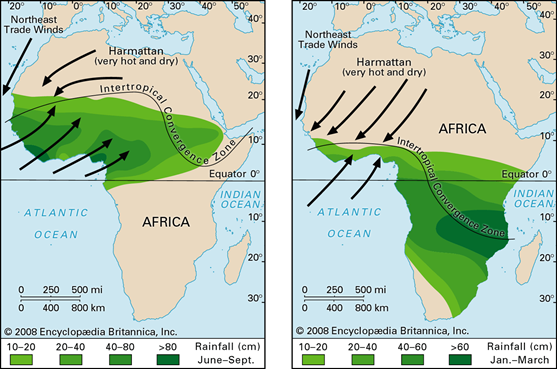

WAM

The WAM is characterised by a reversal of the easterly trade winds to southwesterly and encroachment of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) into west-central Africa during the warm season (June-September). The strength of the warm-season phase of the WAM is important for seasonal hurricane forecasting because it can influence sea surface temperatures within the Atlantic main development regions (MDR) off the Cape verde Islands. Additionally, a stronger warm-season WAM can moisten the region of Africa where African Easterly Waves (origin of most tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin) originate and traverse. The 2020 hurricane season saw one of the strongest warm-season WAM phases on record, leading to anomalously warm SSTs in the MDR, and larger than normal African Easterly Waves.

SST

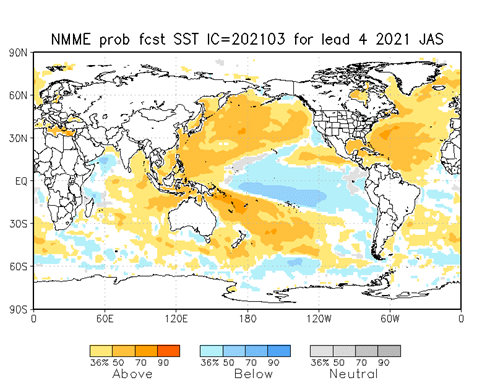

Current modelling guidance using the NCEP North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NNME) model shows a high likelihood of anomalously warm sea surface temperatures across most of the Atlantic Basin during July-September, which would support tropical cyclone activity. This model also favours below average SSTs across the ENSO regions of the Pacific Basin. However, much uncertainty still exists in this forecast and the likely evolution of SSTs will remain ambiguous until later into Spring.

ACE

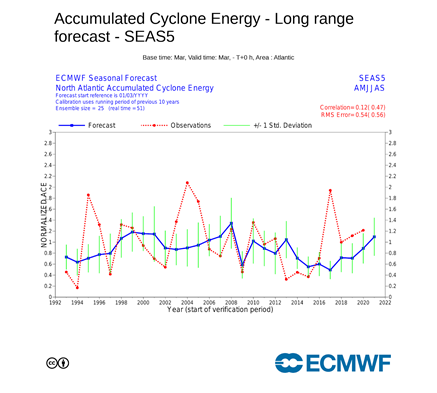

Finally, we will take a look at ACE forecasts from the ECMWF seasonal guidance. ACE is another way meteorologists assess how active a hurricane season will be. It is a metric that takes into account the strength and length of time of individual tropical cyclones during their lifetime. Average ACE for the Atlantic Basin for a season is 105. The latest ECMWF guidance generally shows above average seasonal ACE for the Atlantic basin through September, though a slightly below average season cannot be discounted. It is worth noting seasonal ACE forecasts from the ECMWF model underestimated total ACE for the last five seasons (2016-2020) given the same lead time.

Summary

Most model forecasts indicate an ENSO neutral state perhaps becoming weak La Nina in peak season (September), an active warm-season WAM and warmer than average SSTs across the Atlantic Basin with average seasonal ACE. Given this information, the 2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season will likely be near average to slightly above average. As such the Colorado State University (CSU) Tropical Meteorology Project Team is predicting 17 named storms, 8 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes.

Much uncertainty remains in several aspects of the forecast which will likely not be resolved until later in the spring. Watch out for our follow-up blog in mid May after the NHC, Miami has made their assessment. Meanwhile, the NHC will start issuing Routine Tropical Weather Outlooks commencing 15 May rather than 01 June, as it is not uncommon for tropical cyclones to form on or prior to that date. Lastly, the WMO have announced that the Greek alphabet will no longer be used to name storms when the normal list of names is exhausted. A supplemental list of names will be used instead.

Stay connected and safe.