The 30th of November marked the end of the 2020 Atlantic and the NE and Central Pacific hurricane seasons. While the central Pacific and the NE Pacific had below average seasons, both performed much as predicted by the experts. However, the Atlantic has been unprecedented, setting records in nearly every category except for one surprising statistic – the Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE); more on this later. No hurricane season is exactly like another and each hurricane is a unique event!

Predictions

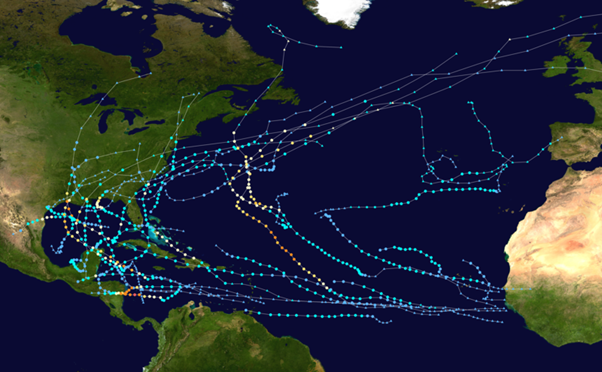

Unusually, all the experts were unanimous preseason in predicting an above average season for the Atlantic, and in general these numbers were further increased mid-season placing 2020 firmly in to the hyperactive bracket. But, no one expected 30 named storms and to surpass the previous record of 28 in 2005. The Greek alphabet had to be used for only the second time in history, extending through to the ninth name on the list, Lota.

Thirteen storms became hurricanes and six were major hurricanes, the second highest number on record, behind only the 15 in 2005. On average, according to NOAA, the Atlantic has 12 named storms, six hurricanes and three major hurricanes. By comparison 2020 doubled these numbers. Since hurricanes can occur outside the traditional season there also remains a slim chance that the bar could be set even higher.

The unanimous predictions preseason were a clear indicator that all of the ingredients needed for an active season would be present in some degree or another. This interrelated set of atmospheric and oceanographic conditions includes amongst others; the ongoing warm Atlantic Multi-Decadel Oscillation (AMO) which makes the North Atlantic Ocean either warmer or cooler every few decades; significantly warmer than average Atlantic sea surface temperatures; a stronger west African monsoon, along with much weaker vertical wind shear; and, a stronger than expected La Niña weather pattern.

Above average

2020 is the fifth year in a row with above average tropical activity attributed to the ongoing warm phase of the AMO, which began in 1995 and could last up to 40 years. However, it is not clear within the scientific community which influence is greater – climate change or the AMO – but either way warmer temperatures in theory lead to more cyclones and greater if not more rapid intensification.

Lacking energy

The ACE score for the Atlantic was far above the normal season in line with expectations, but it fell far short of what would be expected for 30 storms. ACE is the metric used by meteorologists to estimate the intensity of a hurricane season. It is an aggregation of the strength and longevity of all the storms.

Typically, the more ACE there is for a single hurricane season, the more active the season is. For example; 2004 (ACE 227) and 2005 (ACE 245) had comparable levels, but 2005 had 28 named storms while 2004 had only 15 named storms. With 30 named storms so far, 2020 is currently only 178. This is because 2005 had four Category 5 hurricanes, compared to only one so far in 2020 (Lota in mid-November), and more hurricanes overall that were longer lasting. Some of this is because the strongest storms in 2020 formed closer to land, especially the Greek alphabet storms, many of which formed in the Caribbean and so did not have the time to accumulate as much ACE before making landfall.

Late intensity

NHC, Miami define rapid intensification as an increase in the maximum sustained winds of least 30 knots in a 24 –hour period. Ten of 2020’s storms met these criteria tying a record established in 1995. Three storms, Lota, Delta and Eta, intensified by 87 knots (100mph) in less than 36 hours, a phenomenon that researchers say has happened only four times over the last 150 years since records began!

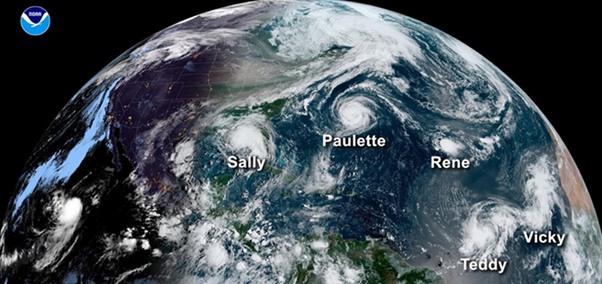

Six of the last seven systems experienced rapid intensification which would be unusual at any time of the year, but significantly these were all Greek alphabet systems occurring late in the season when it normally wanes. This is something not seen before. Lota is the most intense storm on record forming that late in an Atlantic hurricane season. Four of the ten systems also experienced a drop in pressure of more than 40 millibars in 24 hours; again unique to a single season.

Slow moving

According to NOAA past research has shown that hurricanes across the globe are moving slower and stalling more. For 2020, Eta, Zeta, Beta, Sally and Isaias stalled or slowed. The theory for this slowing is that the winds are driven by the temperature difference between the equator and the poles, and as the Arctic warms at a faster rate than the tropics, that temperature difference is reduced and slows the speeds of the steering winds. Slower-moving hurricanes and a warming atmosphere that holds more water means excessive amounts of rainfall and more danger from extreme flooding in coastal regions. Conversely this characteristic leaves a little more margin for ship safety when optimising routing.

Short-lived

By contrast, some of this year’s storms were short-lived and would not have necessarily been recorded without satellites (especially to record a closed circulation) as they generally occurred well away from land and had ‘tropical’ like characteristics: Dolly, Edouard, Josephine, Omar, Wilfred all had less than 30 knots sustained maximum winds but may have briefly produced gusts to tropical storm strength winds before degeneration set in.

Short lived weak systems still represent a threat to shipping, but rapid intensifying storms are especially dangerous as they are challenging to accurately predict. While the track of a tropical cyclone has dramatically improved in recent years, as much as five days in advance, the forecasts for hurricane rapid intensification have improved very little by comparison.

Climate change

In theory a warmer world is likely to see more cyclones but while there is evidence for greater intensity the jury still remains out on the topic of greater frequency. This record breaking Atlantic season is certainly not all down to climate change as some might expect and has not been repeated elsewhere; the Pacific in general has had a below or slightly below average season/year, so globally it has not been a very exceptional year.

The explanation for this hyperactive season is not straightforward. A number of storms showed characteristics that scientists associate with climate change: intensifying rapidly, moving slowly (so producing very large amounts of rainfall). The first half of the season saw quite a few weak systems but this changed in peak season (August to October) and November. This is partially due to development of the stronger than expected La Nina and the extremely warm sea surface temperatures in the Caribbean region, which have been unprecedented going back at least several millennia.

Predicting unpredictability

There is growing evidence the formation of tropical systems is not linear and it may be some of the unprecedented conditions this year reflect a threshold above which frequency (both the total number and length of the season) does increase, albeit it locally rather than more globally. Time and more research will tell. While the ingredients all came together in the Atlantic basin for the 2020 hurricane season with many new records that may stay in the record books for a long time, we can also be sure that climate change will continue to impact future hurricane seasons and weather services will remain vital!

Stay connected and safe.